I'm posting on each of my blogs for New Year's Eve, as a way of thinking through what the past year has been in a number of different aspects of my life. So yes, I'm even posting on this sadly neglected blog. . .

I think if I look back at it, this last year was a year of storytelling. And performing in general. I kicked the year off by being in the Ottawa Women's Slam Championship (and doing better than I'd expected I would; i.e., I didn't fall on my face!) and a lot of my literary stuff this year has been on the stage: I was in an OST Fourth Stage show called "Swindles, Scams and Snake Oil" where I told the story of the Lunar Rogue (a bit of New Brunswick history) and a real-life caper story involving an oil rig and some ill-fated money laundering; I did a set of ghost stories at the Tea Party and got to watch my friend Ruthanne, queen of the spooky story, sitting wide-eyed and creeped out, which I was pretty pleased about; we got the Kymeras back together, and put on our first show in years (Evelyn: a Time Travel Love Story) at Can*Con. And I had the huge honour of being invited to be a part of next summer's 12-hour telling of the Iliad with Ottawa Storytellers and 2 Women Productions.

I think I've gotten over the stage where I insisted I wasn't a storyteller - the storytellers around me just kept saying, well, yeah you are, and inviting me to perform. And every time I was invited to perform, I said yes, because it was always a bit of a different challenge. Can I do ghost stories? Can I do a long story? Let's mix it up with poems and storytelling and see if four voices can pull together a coherent narrative; oh, yeah, and let's make it science fiction poetry and storytelling.

But, I keep thinking, and people keep asking me: how's my writing coming? And I have to say, "well, not that well, really." I started the year out a little swamped with work, learning to juggle self-employment and my personal life. I've fallen out of touch with the local poetry crowd for a whole raft of mostly personal reasons, but also I find with my work schedule it's hard to get out to readings. And if you don't get to readings, you don't get that shot in the arm you need to keep working, keep writing. At least, I don't. I need to be around people who get up early in the morning to go write before work, who have carved out that time. This Christmas I got to talk a little with my niece, who just (well, last spring) finished a Masters in creative writing at McGill, and I envied her the work and time and focus and craft she'd been able to bring to bear on her work.

My own writing has been, largely, blogging (which can be good, but which doesn't get the kind of care and attention and craft that I'm looking for) and journalism. Writing for the Centretown BUZZ has been great in that it forces me to turn out text, but news articles are a whole different thing. I write facts these days, in prosaic words. About as far from poetry as you get, really. But somehow carving out the time to do writing has been harder and harder to do. I don't have evenings to do Creative Writing Playdate with my friend Sean, and in fact the Playdate has gone from a weekly drop-in to a more structured workshop format, because Sean's busy too, and I totally get that. I don't get up early to write (I tried, I really did, I tried, but the flesh is sleepy). And my evenings have increasingly been chomped and digested by email, desultory work on the newspaper and, I will admit it, Facebook.

In the coming year, though, I see that possibly changing. For one thing, the Kymeras' reunion ("We're getting the band back together!" I keep saying) has already made me do some writing, and writing with restraints and requirements. Here's the story, our first meeting said to me, and here's the part you play, and here's the character you inhabit, and do some writing from that place and see what comes out. And so I did, and so I wrote a number of poems in the voice of a dying young Victorian woman.

For another thing, the writing bug has been stirring in the last couple of months. I've churned out some pages I liked. I sat in a pub the other night waiting for a friend and a character did something I hadn't expected him to do: he practically winked at me, then turned tail and ran away from a situation I'd expected him just to talk through. But nope: he saw an out and he rabbited. It didn't do him a lot of good in the long run, because I'm mean to my characters (as you should be) and getting away would have been about as boring as all the talking would have: but the thing was, when he winked at me, I felt it again: what happens when you don't know quite what will happen next.

So it's been a slow year for writing. But there are things in motion. The Iliad will be a challenge of editing, shaping, memory and (scariest) emotional mining and performing; there's a blog post to come about the start of the process and the uncertainty I feel about the journey. But again, I couldn't say no to the opportunity and I'm excited about the road ahead for me and Achilles. The Kymeras plan another show in February, a rerun of Evelyn, and I will get to try my hand at folk tales at the Tea Party that month too. But also, I do intend to try to spend more time writing words that aren't simple fact. Writing words that are beautiful. With luck, getting out to more readings, reading more, listening more, and talking more with writers.

That's the plan.

I like words. I think they should be free to roam in wide open concept barns equipped with nests.

Tuesday, December 31, 2013

Sunday, December 1, 2013

Diving into the Iliad

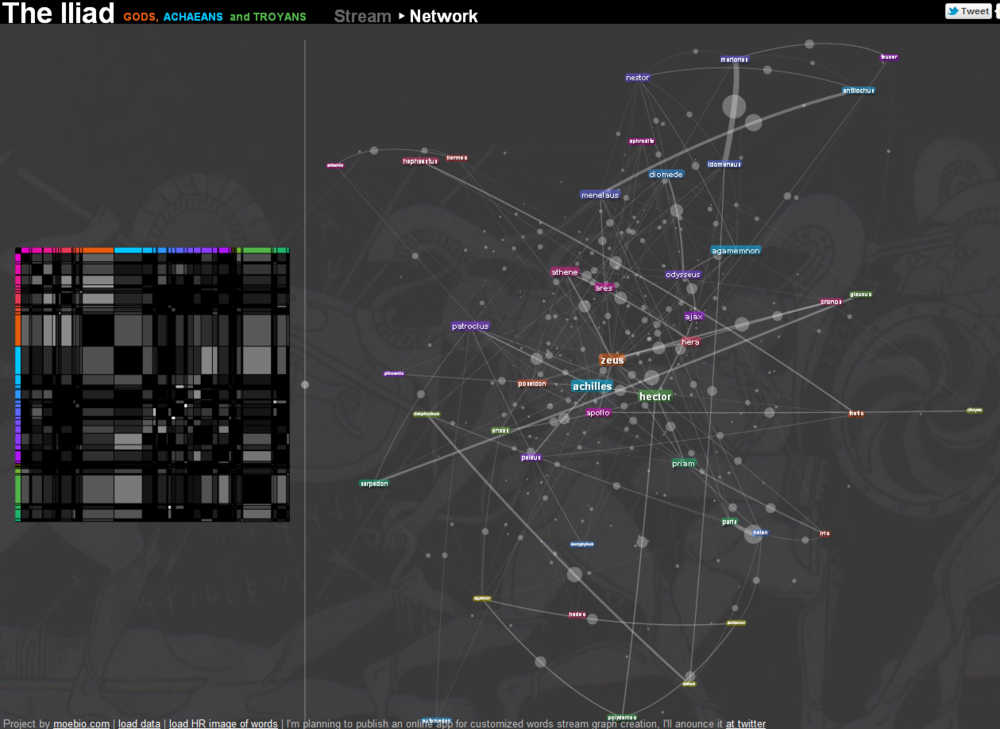

I have to say I'm quite enjoying the Fagles translation of the Iliad, as read by Derek Jacobi. I'm listening to it as a way of reading the Iliad fast, because I have a meeting next weekend with a bunch of other storytellers, which will be step one in a massive project, the aim of which is to tell the whole Iliad in 12 hours next summer. I'll be telling some of it. I have no idea which bit yet... but I'm pretty excited about the process. This will be the biggest storytelling project I've been involved with to date.

Meanwhile, I have to dive right into this story. Here goes!

I like the straightforwardness of this translation; I love Jacobi's plummy voice. Now I just need to get a sense of the whole thing, in time to rationally discuss it for a whole day this weekend. I need an Iliad flow chart. Internet, aid me!

Nope, that didn't help.

Meanwhile, I have to dive right into this story. Here goes!

I like the straightforwardness of this translation; I love Jacobi's plummy voice. Now I just need to get a sense of the whole thing, in time to rationally discuss it for a whole day this weekend. I need an Iliad flow chart. Internet, aid me!

Nope, that didn't help.

Sunday, November 24, 2013

How to survive 50 years (if you're a story)

Yesterday, along with literally millions of other people, I watched The Day of the Doctor - the 50th anniversary episode of Doctor Who. The episode was officially the biggest simulcast of a TV drama ever, broadcast simultaneously in 94 countries, on TV and streaming online, and in 1500 movie theatres in 3D, and I lucked into a ticket because a friend of mine had bought two during the approximately 28-minute period that there were any available, before they sold out.

Doctor Who is the longest-running science fiction show of all time, and one of the longest-running television shows, period, of all time (there may be a soap or two that beat it.) The first episode was aired on November 23, 1963, and no one had a clue what they had on their hands. No one involved in the show then would have had any idea that in fifty years, people would be selling out movie theatres, and gathering at their houses to watch on television or online, all over the world. How could they? They were just making a science fiction show for families to watch; something with a bit of an educational bent, catching the SF wave, on a budget, for the BBC.

Today, though, I bet BBC executives are doing happy dances. Doctor Who is probably one of the BBC's biggest exports and cash generators. The revenue generated from this 50th anniversary release must be impressive. What other television show could have fans paying movie theatre prices to watch a special episode? What other television show could cause people to speculate that the Hunger Games sequel might suffer a dip in opening weekend box office because the audiences were busy watching Doctor Who? What did advertisers pay the BBC to be featured on their mini episodes, released online leading up to the special, or to be featured on the big screen before the broadcast?

And - has Doctor Who set a precedent, broken ground in how television gets presented? Is this where "event television" might go? Given the success of this, are we likely to see, say, the series finale of Game of Thrones broadcast to theatres?

I'm a pretty big fan of Doctor Who. I watched it as a kid in the eighties, but not seriously - I remember catching it when I happened to have the TV on and it was playing on the public broadcasting network. I loved it but for some reason never knew quite when it would be on. I remember a few vague scenes, mostly of the Doctor and whichever companion he was with running around through slate quarries - I mean, alien landscapes - being chased by Daleks. I definitely remember the Daleks. I think any kid that saw them does. Today I heard an interview with Peter Davison, the fifth actor to play the Doctor, who confirmed that yes, even in real life when you know they're props, Daleks are unnerving. It's the way they glide.

And I remember that I thought the theme music was creepy, and cool, and strangely sad, all in one. Oh, and that endless looping chrome tunnel that the title credits appeared over was mesmerizing to me. Also, in those years there were writers and actors that cemented the show's future: the years with Tom Baker as the Doctor and Douglas Adams on the writing team are probably responsible for the show's survival to 2013.

I got back into the show, like a lot of people, with the "new Who." It started up in 2005, but annoyed with reboots and remakes, it took me a while to watch it: I resisted as my friends started getting hooked around me. But I started in around the third season. My first episode, I think, was "Smith and Jones," in which the Doctor's second (well, second in terms of the new series) "companion" is introduced, Dr. Martha Jones. She's in a hospital that gets unexpectedly relocated to the moon. Then invaded by space cops with the heads of talking rhinoceri. Then this frenetic skinny guy with spiky brown hair in a suit and running shoes shows up and, among other things, absorbs a room full of radiation into his body, then expels it into his shoe, kicks the shoe off, and keeps running around barefoot for the rest of the episode, while managing to save everyone. He looked like he might be a member of some British hipster band, and I remember thinking, "This guy? Really? Doctor Who?"

And yes. That guy. Really. Doctor Who. David Tennant (the tenth actor to play the role: there have, as of yesterday, officially been thirteen) hooked me. Then I started collecting the box sets - the first season, with Christopher Eccleston in the role, then the Tennant years, eventually collecting as fast as they came out and watching them on broadcast at the same time. I'd been making sure I caught every week's episode for a while by the time it was Matt Smith's turn in the TARDIS. And I was, by that point, a dedicated, one might say fanatical, Whovian, with a collection of all the extant "20th century" episodes from 1963 to the ill-fated Fox/BBC co-pro movie of 1996, a handful of the audio dramas, and a range of buttons, T-shirts, patches, and toys.

So, we get to why I'm writing about this. One of the things that fascinates me about this show is that it shouldn't survive. It shouldn't be popular. Other blockbuster science fiction shows, like Star Trek, make a lot of hay out of scientific explanations of their gadgets and gizmos. What Trekker doesn't have a blueprint of the Enterprise somewhere, detailing exactly where the kitchens and toilets and turbolifts are? There's a hunger for explanation, for categorization, for everything to be explained, in the geek world. Think of things like Dungeons and Dragons, where everything has a set of statistics.

Doctor Who, in contrast, breezily ignores explanations. What's the inside of the TARDIS look like, other than the main console room where everything happens? Well, it looks like whatever the TARDIS (which, it should be explained, is semi-sentient, sometimes) wants it to. Why does it look like a police phone box on the outside? Because it's broken. (A writer once tried to write some technobabble to explain the shape, back in 1963: it was lame and pseudomystical, and the then show runner, Verity Lambert, chucked it and instead declared that the TARDIS was supposed to change appearance to blend in with the local surroundings as camouflage, but the circuit was stuck. It's stayed stuck for 50 years now. Though now, occasionally, it can be invisible.) Does the Doctor have any special powers or abilities? Only when the plot requires it. Does he need to be clairvoyant, telepathic, a hypnotist, an expert swordsman? He can be, when it's required, but it's not a character point. What does that sonic screwdriver he carries around do? Whatever makes the story more fun. What are its limitations? Ditto.

This kind of rule-chucking flies in the face of almost everything else in science fiction and fantasy. One of the main rules of worldbuilding is that your world and setting and the science and/or magic you use needs to be consistent. Then Doctor Who comes along and tells you that hand-waving isn't a narrative failing, it's the main joy of the show. Although they said in 1964 that the Cybermen came from Earth's hidden sister planet Mondass, they're actually, now, from a parallel universe. And that's okay. And you know how we said Daleks worked on static electricity and so needed to be in contact with a metal floor? They got better. Why doesn't the human race remember about the dozens of times they've been invaded or subjugated or otherwise nearly wiped out? We're thick. Or there was a time paradox thing and we all forgot. Know how the Doctor absorbed all that radiation and said it was child's play? Well, for this story we need him to die of radiation poisoning, so he can't do that anymore. No reason.

This should infuriate the sort of person who wants blueprints of the Enterprise. Instead, they love it. They make up all their own rules and laws to cover all the gaps and inconsistencies. Or, like me, they celebrate the sheer loopiness of it, and look at it this way: Doctor Who is about stories. The main character is a story. Occasionally, he knows it. The show even comments on its own story-ness, at times. (The glee with which the Doctor and his companions often discover that they're in a particularly new story is always fun. In one episode, after narrowly escaping the monster of the week, the Doctor and Rose turn to each other. "I tell you what, though," Rose says, excitedly. "Werewolves!" He answers, "I know!" with a huge how-cool-is-that grin.) One of my personal favorites is when there's a plot point that turns on "stet" radiation: "Never heard of it," the Doctor says. "You wouldn't want to," another character says. Meanwhile, as an editor, I stifle a giggle: "stet" is proofreading notation indicating that an editor's change needs to be reversed: the thing that was eliminated gets restored. The next bit of the plot involves a character who can't die. Maybe it's just an editor thing, but it makes me grin.

Also, the show shouldn't survive because the central protagonist actually changes his entire face and personality on a regular basis. Every so often, the Doctor is killed. And when that happens, he transforms into another man. With the same memories, but a different personality. The first time they did this, when the first Doctor, William Hartnell, was sick and couldn't continue in the role, must have been a leap. It's still a bit strange. But now, it's part of the culture. Those of us that have known the show a long time - I was watching when Tom Baker gave way to Peter Davison in the mid-eighties - get to feel a little smug whenever a changeover happens, and we watch the newer fans mourn the loss of "their" Doctor, and vilify the new one for whatever they see as his faults.

Meanwhile, those of us who have been through a few regenerations have taken it as part of the fandom. Who will the new Doctor be? How will he change the tone? Rumours and speculations about the new actor will fly. We'll watch ourselves go through the phases: mourning the loss of an actor we loved in the role, settling in with the new guy, deciding what we think of him, finding the through lines that let us, mentally, tie him to his predecessors, and, eventually, learning to love some aspect of the way he plays the character. Yesterday, in the theatre, we got a second-long flash-cameo of the upcoming actor, Peter Capaldi (Matt Smith is leaving the role after the Christmas special this year), and there were cheers in the theatre: we're sad to see Smith go, but we're excited to see how the character will change.

Because although the actor changes, the story keeps going. And it can only keep going by being loopy and inconsistent and allowing us to be okay with that. In fact, encouraging us to embrace it. Every time an actor leaves - a Doctor or a companion - you think about the stories that you didn't get to see happen with them, but the story itself is not over. You can go back, if you want to see Tom Baker's bug-eyed strangeness, or Peter Davison's big-brother kindness, or William Hartnell's crusty tetchiness, or Paul McGann's Romantic elegance, or the bottled anger of Christopher Eccleston. They're all still there. You won't get any more stories with them, and that's sad. But you'll get new stories with this new guy, and he'll be great in his own way, and he will, ever so often, also remind you of the past Doctors.

And in that way it's a lot like life.

Thursday, October 24, 2013

Writers Festival kicks off

I just remembered I didn't actually report in about Detroit. Will do: soon.

Tonight I ran to CKCU to do an episode of Literary Landscapes, talking about the upcoming funding drive and the Writers Festival, which just kicked off tonight with a lovely event with Jim Cuddy and Greg Keelor from Blue Rodeo (which I scurried off to after the show was over) - a look back at the creation of the iconic album Five Days in July, with messages and interviews from the musicians who were part of it, conversations about the creation of the songs, and covers performed by various musicians, as well as by Jim and Greg. Very cool.

(It occurred to me, sitting in the overflow room with my friend Terry, that I'm fairly certain I went to a Blue Rodeo concert on what was probably my very first - and therefore pretty awkward - date. Which made the evening a little surreal for a moment or three.)

Anyway. It seems to me that these songwriters' events - curated by Alan Neal from CBC's All in a Day - are a unique beast, and really Writersfest is the only place I can imagine them working. Which they do, marvellously - people do want to hear the stories behind the songs, and hear the songs, and the cross-pollenation that Alan manages to get by inviting - and getting - people like Jully Black and Mike Dubue to, say, come cover some Blue Rodeo tunes on stage means that you're getting a really unique event. Not a concert, not an Inside the Artist's Studio kind of thing; something in between the two, with a kitchen party vibe thrown in too, as the musicians start to relax and jam and play with each other.

The Festival continues tomorrow: I'm taking George Elliott Clarke to a couple of schools, and the evening's packed with coolness, including a launch by David O'Meara, Stephen Brockwell reading from his new book, and the Newlove Awards...

Tonight I ran to CKCU to do an episode of Literary Landscapes, talking about the upcoming funding drive and the Writers Festival, which just kicked off tonight with a lovely event with Jim Cuddy and Greg Keelor from Blue Rodeo (which I scurried off to after the show was over) - a look back at the creation of the iconic album Five Days in July, with messages and interviews from the musicians who were part of it, conversations about the creation of the songs, and covers performed by various musicians, as well as by Jim and Greg. Very cool.

(It occurred to me, sitting in the overflow room with my friend Terry, that I'm fairly certain I went to a Blue Rodeo concert on what was probably my very first - and therefore pretty awkward - date. Which made the evening a little surreal for a moment or three.)

Anyway. It seems to me that these songwriters' events - curated by Alan Neal from CBC's All in a Day - are a unique beast, and really Writersfest is the only place I can imagine them working. Which they do, marvellously - people do want to hear the stories behind the songs, and hear the songs, and the cross-pollenation that Alan manages to get by inviting - and getting - people like Jully Black and Mike Dubue to, say, come cover some Blue Rodeo tunes on stage means that you're getting a really unique event. Not a concert, not an Inside the Artist's Studio kind of thing; something in between the two, with a kitchen party vibe thrown in too, as the musicians start to relax and jam and play with each other.

The Festival continues tomorrow: I'm taking George Elliott Clarke to a couple of schools, and the evening's packed with coolness, including a launch by David O'Meara, Stephen Brockwell reading from his new book, and the Newlove Awards...

Thursday, September 26, 2013

Maybe someday you can go to Detroit.

|

| From the inimitable Uncle Shelby's ABZ. Shel Silverstein is a god. |

It's kind of literary, right? Tomorrow I'm heading out of town in the afternoon with my friend Jex to drive to Detroit for the weekend to see an exhibit of Dr. Seuss's hats. No, really.

I admit it's a pretty random thing to do. But what's life for, if not to do random things with?

I'll report in.

Wednesday, September 25, 2013

Collaborating kick start

The Kymeras' show at CAN*CON (Evelyn: A Time Travel Love Story) is coming up fast. We met up this weekend to run through the first real version of the show and figure out exactly what order things would go in.

I'm in an interesting position in this process. We're expanding a poem of Sean's into a full show. Marie and Ruthanne are filling in details of the narrator's story. I was given pretty much anything to do on my part, and in the first meeting it was suggested I could fill in the other voice - that of the narrator's wife. That way the two "characters" are voiced by poets while the narrative details are done by the storytellers.

But that meant I had to go home and write some poems about a very specific thing, in a very specific voice. It was tricky - I wrote a lot of fragmentary pieces which I then stuck together, or picked up and expanded. My character is only in the story in a strange, sort of disjointed way, so I wound up writing her voice in a series of short journal notes and fragments of letters and thought processes. Her speaking, in her mind, to either her husband or herself. When I brought them to the second meeting I thought I had a bunch of crap. But then we started shaping the story up, and it started to take a form with our four narratives interrupting each other and interweaving. We went off so the storytellers could craft their bits and Sean and I could tinker with our poems. Sean wrote a longer, more satisfying denouement and cut the poem into sections that could be interrupted by story. And I poked at my little poem fragments and couldn't really see how to make them into anything else.

But then this weekend we met again. I still just had my little fragments, and one full poem that I was happy-ish with. But magic happened. As we started the rough runthrough - Sean reading his intro, then Marie walking us through her story framework, and me reading out the poems I thought would go in various places - things started to fall into place. I still only had my fragments for the second half, but while people were reading through their parts I started crossing stuff out, drawing in arrows, reshuffling everything on my page. Between me and Ruthanne - covering most of the second half of the show - we rearranged the stuff I'd written, fit in in between Ruthanne's short vignettes, and suddenly there were all these resonances bouncing around between the different voices and threads of the story. I could actually see how the bits I'd written related to each other, where they could fit together into more coherent wholes.

And suddenly I felt more like writing than I have in a long time. Having some other brains around to bounce things off of, yes, but more importantly, working with those other brains on an actual collaboration got my brain engine rumbling. And I remembered, again, how much I like working with the Kymeras.

Good news, by the way: you can now buy a day pass for Saturday evening at CAN*CON, so you can come for just the evening's shows, including Evelyn.

I'm in an interesting position in this process. We're expanding a poem of Sean's into a full show. Marie and Ruthanne are filling in details of the narrator's story. I was given pretty much anything to do on my part, and in the first meeting it was suggested I could fill in the other voice - that of the narrator's wife. That way the two "characters" are voiced by poets while the narrative details are done by the storytellers.

But that meant I had to go home and write some poems about a very specific thing, in a very specific voice. It was tricky - I wrote a lot of fragmentary pieces which I then stuck together, or picked up and expanded. My character is only in the story in a strange, sort of disjointed way, so I wound up writing her voice in a series of short journal notes and fragments of letters and thought processes. Her speaking, in her mind, to either her husband or herself. When I brought them to the second meeting I thought I had a bunch of crap. But then we started shaping the story up, and it started to take a form with our four narratives interrupting each other and interweaving. We went off so the storytellers could craft their bits and Sean and I could tinker with our poems. Sean wrote a longer, more satisfying denouement and cut the poem into sections that could be interrupted by story. And I poked at my little poem fragments and couldn't really see how to make them into anything else.

But then this weekend we met again. I still just had my little fragments, and one full poem that I was happy-ish with. But magic happened. As we started the rough runthrough - Sean reading his intro, then Marie walking us through her story framework, and me reading out the poems I thought would go in various places - things started to fall into place. I still only had my fragments for the second half, but while people were reading through their parts I started crossing stuff out, drawing in arrows, reshuffling everything on my page. Between me and Ruthanne - covering most of the second half of the show - we rearranged the stuff I'd written, fit in in between Ruthanne's short vignettes, and suddenly there were all these resonances bouncing around between the different voices and threads of the story. I could actually see how the bits I'd written related to each other, where they could fit together into more coherent wholes.

And suddenly I felt more like writing than I have in a long time. Having some other brains around to bounce things off of, yes, but more importantly, working with those other brains on an actual collaboration got my brain engine rumbling. And I remembered, again, how much I like working with the Kymeras.

Good news, by the way: you can now buy a day pass for Saturday evening at CAN*CON, so you can come for just the evening's shows, including Evelyn.

Wednesday, September 18, 2013

Revisiting Watership Down, and some thoughts about stories

A while ago, a friend of mine started "The Most Awesome Book Club Ever": a book club where the idea is to read books that are considered "Great Books" that you might have been asked to read in school but somehow missed. Books you're supposed to have read. Things like War and Peace, or the Odyssey, or The Origin of Species. (Which was our first book, actually. I didn't like it that much.)

I think the characters being simple is a strength, rather than a weakness, in the book. They're already talking rabbits, after all. We're already dealing with a metaphor, or a myth, or an allegory, or something. The subthread about storytelling underpins that. So there's never really much question that Hazel, the leader, is going to be the leader. He's a perfect leader - not particularly strong or clever himself but able to see the skill sets at his disposal and put them together, and also able to read a mood and know how much he can ask of his people. In the same way that you know who Hazel is because you know the "leader" archetype, you also know what to expect of the rest, and it's satisfying when they fill those roles well: Bigwig being tough and loyal and self-sacrificing, Blackberry thinking up the clever plan, Fiver never, ever, once having a bad feeling that turned out just to be a badly digested carrot or something.

This month's book is Watership Down, by Richard Adams. I've read it before: in fact, I grew up with it. I went to see the movie when I was seven: my family was living in Indiana at the time, and I think it was screened at the university there, but I don't really remember - I do remember images from the movie, some of them quite terrifying, and some of them quite beautiful. I think my parents read me the book first, as part of our usual bedtime stories. (My parents read me all kinds of books at bedtime, from Watership Down to The Lord of the Rings to Robinson Crusoe, and if they had scary bits, we dealt with that. In various ways. Depending on the book.) So when I was a kid, I sometimes pretended to be Hazel or Fiver (usually Fiver: I always liked psychic characters) and I had nightmares about the Black Rabbit of Inlé.

And I read it again, this week. I just finished it. Correction: I just finished wiping the tears off my face, after finishing it. How dare a book about rabbits do that to me?

I re-read another of Adams's books recently, The Plague Dogs, because I'd just been to the Lake District, where it's set, and so I had the literary equivalent of an earworm. They're very different books, and for a while I thought I liked The Plague Dogs more. It's certainly more aimed at adults. It's also preachier. Angrier, maybe. In Plague Dogs Adams goes off on long flights of reference, paraphrasing chunks of Shakespeare and Ovid. In part I think it's deliberate: he's echoing the hyper-associative, disjointed internal world of his insane protagonist Snitter, a dog who's undergone brain surgery as part of an experiment. But it has always struck me as a bit self-indulgent. It's a satirical voice, and being satirical can often mean getting self-indulgent. You can read it as Adams being arch and sarcastically angry and having fun with his overblown language, and I did, and I do like The Plague Dogs. But now that I've reread Watership Down, I've revised my best-Richard-Adams book order. Watership wins, hands down.

It's his economy in Watership Down. It's a long book, sure, but because I read it as a kid, it all seemed to take longer (reading is so immersive when you're ten or so). I realized, this time around, that in fact a whole lot happens in a few pages. There's so much detail packed in, neatly, unnoticeably, that it feels longer. The friend that started the book club mentioned, as she was reading it, how information like "human activity causes background noise that disturbs animals" can be delivered almost indetectably by describing the silence of Watership Down, where our heroes establish their new home. Points like "domestication takes something vital away from species that are meant to be wild" are illustrated rather than stated, by the strange, semi-domesticated Cowslip and his warren and the hutch rabbits Hazel frees, who are so inept.

And there's the subthread about storytelling. Alongside Hazel and his group's adventures, there's a counterpoint series of folktales about El-ahrairah, the rabbit trickster hero. To Adams's rabbits, storytelling is a central social glue. Rabbits love a good story, well told, and while it's being told, they live it. They spread news by telling stories - when Captain Holly arrives at Watership Down, having narrowly escaped the destruction of their old warren, they wait until they can all gather and he can tell the story as a story before anyone asks him for details about what happened to him. Then, when he does, all of the rabbits suffer through the same feelings and experiences as he did, and by doing that, they get their grief out and over with. The idea, I think, is that for a species with "a thousand enemies," the best way to learn survival skills is to tell these stories: you can learn from a story without running the risk of being killed by a fox or something.

Tellingly, in the warrens in the book where the rabbits are not living natural lives - in what I call "the Stepford warren" where the rabbits are actually being semidomesticated so they can be trapped for fur and meat, and in totalitarian Efrafa - the rabbits no longer tell stories. Instead, they recite poetry. Instead of sharing an external social narrative, they share an internal, psychological narrative. They turn inward. (But, to be fair to the poets, in both of those warrens, poetry is also an act of subversion, of saying things that are forbidden.)

Adams' rabbits lead an immediate kind of life, where real threats and dangers force them to be clever and fast and strong: he may be hinting that we, as humans, lead a life much more like that of the creatures we domesticate, where our stories don't teach, our art is internal and reflective, and our instincts are dulled. He certainly uses the two dystopian warrens to show us two different outcomes of surrendering your self-determination. In one, luxury stultifies a whole culture: in the other, a dictatorship takes over and imposes a rigid, unnatural way of life.

Adams' rabbits lead an immediate kind of life, where real threats and dangers force them to be clever and fast and strong: he may be hinting that we, as humans, lead a life much more like that of the creatures we domesticate, where our stories don't teach, our art is internal and reflective, and our instincts are dulled. He certainly uses the two dystopian warrens to show us two different outcomes of surrendering your self-determination. In one, luxury stultifies a whole culture: in the other, a dictatorship takes over and imposes a rigid, unnatural way of life.

And yes, the characters are simple. I think of them as the classic adventuring party from a fantasy. You've got your born leader, your staunch and loyal lieutenant, the clever one, the mystic, the storyteller and charmer, a couple of rank and file types, and the one that needs protecting.

I think the characters being simple is a strength, rather than a weakness, in the book. They're already talking rabbits, after all. We're already dealing with a metaphor, or a myth, or an allegory, or something. The subthread about storytelling underpins that. So there's never really much question that Hazel, the leader, is going to be the leader. He's a perfect leader - not particularly strong or clever himself but able to see the skill sets at his disposal and put them together, and also able to read a mood and know how much he can ask of his people. In the same way that you know who Hazel is because you know the "leader" archetype, you also know what to expect of the rest, and it's satisfying when they fill those roles well: Bigwig being tough and loyal and self-sacrificing, Blackberry thinking up the clever plan, Fiver never, ever, once having a bad feeling that turned out just to be a badly digested carrot or something.

By halfway through the book, you can't help seeing that these rabbits we're reading about are living out an El-ahrairah story. They even start reflecting on it themselves. Which brings the whole subtheme of storytelling back around, rather neatly. And in the final pages, when El-ahrairah comes to take Hazel away to join the pantheon of stories. . . well, that's the bit where I had to stop and blink and wipe away the tears. Maybe I'm sentimental, but "our children's children will hear a good story" (as Hazel said to Bigwig), resonates with me. "It matters not if you live one day, so long as your deeds live on after you," is the ancient Irish saying.

I'm looking forward to the conversation when the Most Awesome Book Club Ever gets together to talk about this one. Because I know that alongside talking about the different dystopias and false utopias the rabbits encounter, and the ecological points that are made, and the characterization, and the plot arc, there will be the times when one of us will say, "And there was the bit where Bigwig was standing in the tunnel, saying, 'My Chief Rabbit told me to defend this tunnel, and I will,' and Woundwort's thinking, 'Shit, if he's not the Chief Rabbit, then how big must his Chief Rabbit be?!?'" or something like that. We'll share our favorite bits of the story with each other. We'll tell them again to each other. Because that's what stories do, it's what they're for.

And it had never occurred to me before, but I think that's a big part of what Watership Down is all about.

I'm looking forward to the conversation when the Most Awesome Book Club Ever gets together to talk about this one. Because I know that alongside talking about the different dystopias and false utopias the rabbits encounter, and the ecological points that are made, and the characterization, and the plot arc, there will be the times when one of us will say, "And there was the bit where Bigwig was standing in the tunnel, saying, 'My Chief Rabbit told me to defend this tunnel, and I will,' and Woundwort's thinking, 'Shit, if he's not the Chief Rabbit, then how big must his Chief Rabbit be?!?'" or something like that. We'll share our favorite bits of the story with each other. We'll tell them again to each other. Because that's what stories do, it's what they're for.

And it had never occurred to me before, but I think that's a big part of what Watership Down is all about.

Tuesday, September 17, 2013

Not being at all nice in a review, which is possibly a first for me.

I suppose it was inevitable.

I got bored this afternoon. And I've just discovered readanybook.com, where you can read a bunch of books online if you're not picky about format. And because I was bored I read the first page of the first book presented to me, which happened to be Twilight. Hey, I had to look. And I thought, okay. Maybe I should see what all the fuss was about. Expectations not high, but if I'm going to denounce a thing, I suppose I should at least have read it.

I tried, I really did, because goddamn it there has to be some reason so many people were so crazy about this book . . . but about a third of the way through it I just couldn't take any more.

It really is as godawful as people say. It is unspeakable. How in the name of all that is holy was this a bestseller?

Not only that, it really is poisonous in terms of what it says to young women about what's desirable in a man. Every single thing about Edward and how he treats and reacts to Bella should be sending off a million alarm bells screaming this guy is a psycho stalker, potential abuser, control freak with anger issues, big woop woop woop alarm klaxons going off avoid avoid avoid. Anyone - "perfect," "alabaster," "flawless," or not - who behaved like this around any rational female would instantly get filed under "keep-911-on-speed-dial." Even in high school. But no. She's irrevocably in love with him, pretty much immediately, because... he's perfect. A fact of which we're reminded about three times a page (note the above references to "perfect alabaster flawlessness").

So, in fact, every single thing about Bella also sends off huge alarm bells for me. She's a painful Mary Sue. She has no internal life outside of Edward, and even that is unconvincing. She doesn't act like a teenager, or like an actual human being for that matter. And apparently thinking it's hot to be terrified of someone (who's a perfect alabaster sparkly god who wants to kill you but that's totally okay because, you know, he's perfect) isn't a sign of any deepseated personality disorders at all.

On top of all that the writing is tooth-achingly dull and plodding.

Augh. AUGH. I have to go bleach my brain now.

I got bored this afternoon. And I've just discovered readanybook.com, where you can read a bunch of books online if you're not picky about format. And because I was bored I read the first page of the first book presented to me, which happened to be Twilight. Hey, I had to look. And I thought, okay. Maybe I should see what all the fuss was about. Expectations not high, but if I'm going to denounce a thing, I suppose I should at least have read it.

I tried, I really did, because goddamn it there has to be some reason so many people were so crazy about this book . . . but about a third of the way through it I just couldn't take any more.

It really is as godawful as people say. It is unspeakable. How in the name of all that is holy was this a bestseller?

Not only that, it really is poisonous in terms of what it says to young women about what's desirable in a man. Every single thing about Edward and how he treats and reacts to Bella should be sending off a million alarm bells screaming this guy is a psycho stalker, potential abuser, control freak with anger issues, big woop woop woop alarm klaxons going off avoid avoid avoid. Anyone - "perfect," "alabaster," "flawless," or not - who behaved like this around any rational female would instantly get filed under "keep-911-on-speed-dial." Even in high school. But no. She's irrevocably in love with him, pretty much immediately, because... he's perfect. A fact of which we're reminded about three times a page (note the above references to "perfect alabaster flawlessness").

So, in fact, every single thing about Bella also sends off huge alarm bells for me. She's a painful Mary Sue. She has no internal life outside of Edward, and even that is unconvincing. She doesn't act like a teenager, or like an actual human being for that matter. And apparently thinking it's hot to be terrified of someone (who's a perfect alabaster sparkly god who wants to kill you but that's totally okay because, you know, he's perfect) isn't a sign of any deepseated personality disorders at all.

On top of all that the writing is tooth-achingly dull and plodding.

Augh. AUGH. I have to go bleach my brain now.

Saturday, September 14, 2013

Getting the band back together!

I'm pretty excited. the Kymeras got invited, a while back, to perform at CanCon in October. We've really, for real, started putting the show together and I can't wait to see the final product. It'll be the first Kymeras show in... frankly, in donkey's years. I'm really happy we're performing together again.

This being us, of course, we weren't content to go the easy route and just put together a show where Sean and I do poetry, Ruthanne and Marie do some stories, and they all have the same general theme. No. This being us, we started spitballing some ideas, and now we've got ourselves embroiled in a multiple-voiced, multiple-faceted, single-arc story that will take us an hour or so to tell: a story spun out of a beautiful poem Sean performed at our steampunk show a couple of years ago; a story about love and time travel.

It's actually been a long time since I wrote much of anything, other than blog posts and news articles, and it was hard and effortful and eventually encouraging to go back to it. To sit down in front of the computer and get through that horrible first fifteen minutes or so where you really just want to go open the Facebook window and look at your friends' posts and get frustrated that no one has posted anything fascinating in the twenty minutes since the last time you checked and . . . well, you know. It's not pretty. I sit there staring at the screen, write a sentence or two, then delete them again, then lose focus. Then remember I should probably check that the cats' water bowl's been topped up.

But, in writing for this show, I got to break through that phase and actually start creating again. The other night, I actually wound up staying up late writing (haven't done that in so long). And then I went to our first real show-structure meeting today, where we took the stories and poems we've been working on and read them to each other and started figuring out exactly what would go where, and I admit I walked in thinking, as I usually do, "well, I've brought a load of crap." But I knew I was going to have to read them out loud. It was hard to work up to.

Funny how reluctant I can be to perform in front of three friends, rather than a room of a hundred strangers. And before I read, Sean was talking about what he imagined my part being - I'm basically playing the role of a character in his original poem - and it didn't seem to match up at all. Which made me feel a bit insecure - here I'd written my couple of crappy poems and they didn't do what they needed to do and . . . ah hell. But then the others made me read them. And when I was finished, Sean said, "You need to get over this insecurity thing, that was perfect, that was exactly what I was talking about, it was beautiful," and a bunch of other nice things, and I felt a lot better.

And besides. . . Man, it's fun to collaborate with these folks. For some reason, Sean and Ruthanne and Marie and I collaborate really well. And we're at our best when we're putting together a show like this one - one that's a cohesive tale or an arc, one where there's a certain amount of theatricality and staging involved (in this show, Marie and Ruthanne will act as narrators: Sean and I will be in first person, inhabiting the characters of John and Evelyn, and there's some staging to enhance that idea). As we started to talk through the show structure and the stories Marie and Ruthanne were crafting, I caught myself thinking, "Wouldn't it be cool if we did X?" only to have someone suggest it a moment later, or have that facet appear in the story they were planning. It was almost uncanny.

So yeah - it is great to have the band back together. We're planning this show, for October 5, and a reprise of our winter solstice show for a house concert in December, and already talking about touring Evelyn in 2014. It's pretty exciting.

Sunday, March 10, 2013

Hilarity (and some surprise) at the Haiku Death Match

The CPC's first Ottawa Haiku Death Match went down last night. And if you weren't there. . . sorry. You missed a hell of a good time.

I'd heard about other Haiku Death Matches before, and when I interviewed Rusty Priske, the Slam Master, about it a couple of weeks ago on Literary Landscape, we talked about what kind of haiku to expect. A haiku's short, and if you're going up against each other in an audience-judged competition, you go for pithy, funny, snappy, right? In Vancouver, I've been told, the competition is dominated by sex jokes.

When I got to the Mercury Lounge, they were tying balloons to the wrists of all the competitors who signed up. People were walking around counting syllables on their fingers and reading through notebooks.

Ten people were eventually signed on to the lists. I'd intended to sit back and enjoy the show, but then was asked to be a judge. "You don't have to give a grade," Brad said. "You just have to pick one poem or the other."

Well, how hard can that be? I thought to myself. I've judged at slams before but I really have a hard time giving a number grade to poetry.

I was a fool. Having to pick between two haiku was, at times, astonishingly difficult.

The competition was gleefully hosted by Brad Morden, who announced the rules: Two names would be drawn from a hat. Those two "haiku warriors" would come to the stage. Each would perform a haiku, and the judges would choose a winner (by flashing either a copy of the latest Capital Slam CD or the flyer for next week's VERSeFest). Best two out of three would take the bout. Once you lost two bouts. . . your balloon was popped. Ceremoniously. To a chorus of cries from the audience of "Aww... no! NO!" as Brad proclaimed, "We live and die by the pen!" and popped the balloon with a ballpoint.

Another rule: total silence during the bout. You could clap for the "haiku warriors" when they were called up (and as the night went on, you could hear the reaction from the audience when a particularly strong pair got called), but then Brad would call out, 'SILENCE!" and you were supposed to be quiet as the haiku, some of which were really funny, were read. This, of course, only served to heighten the hilarity as people either stifled laughs, or defied the silence rule and laughed out loud or shouted things.

Meanwhile, behind the competition, classical Japanese music played.

It was hilarious.

The haiku had a wide range: from the expected sex jokes, through pop culture references, to the stereotypical lyrical and evocative image. Some haiku warriors made their stuff up on the spot: "I love cats. Too much. / My arms are full of scratches. / Kitties, love me back!"

Others brought their books, and flipped through them madly trying to choose the right response. And then came the first balloon death. "No mercy at the death match!" Brad roared. "We live and die by the pen!"

I get the feeling he was enjoying himself.

Finally there were only four poets left standing, and we had a break. I had been surprised by what I was hearing. As a judge, I had to make a snap decision every time. The poems could be radically different, or both in similar modes: either way, it would be a serious bitch deciding which to give the win to. There were funny poems about zombies, or wistful poems about lost loves, or snappy self-referential poems - I liked Rusty's "haiku trash talking" poem, for one - or 'deep thoughts' poems (a lot of these brought out by a newcomer to the CPC scene, who went by K. G., an older man who got up to the mike each time with a sort of gravitas, and a measured, dignified, Caribbean accent, that inevitably slew the other poets, particularly if they brought a funny poem. We talked about it afterwards: If you were up against him, and all you had was a dick joke, you inevitably sounded trivial compared to his meditations on the human condition. You had to have one hell of a good dick joke to beat that.)

Which is the surprise, for me. I knew that in the Vancouver scene, the dick joke would normally win. As the night went on I saw the judging going in strange directions - not always in favor of the deep stuff, but definitely resistant to the cheap shot. I know I was giving more points to people whose phrasing sounded natural (it takes more skill to make a 5-7-5 syllable pattern sound like normal talk than to drop out the odd article because it saves a syllable, and I consciously rewarded that). I think my fellow judges were doing the same thing. Top marks, generally, would go to witty AND insightful, which was hard to go for.

My money, if I had had money riding on this thing, would have been on Kevin Matthews. He's the Master of Many Genres, and I've seen him do everything from slam to avant-garde. He's good at brevity and epigrammatic wit. And I know from his slam poems that he can do funny and perceptive at the same time. I'd have backed Kevin. And, when it came down to the final four, he was in the ranks.

It came down in the end to Kevin and K. G.

And, as it turned out, K. G. took the last bout. To cries for mercy from the audience, Brad popped Kevin's balloon: then the audience called for a victory haiku from K. G., which he read from his chapbook. (He also insisted on having his balloon popped as well, while the audience shouted, "Let him keep it!" But I thought it was fitting the whole pseudo-bushido atmosphere. All things are ephemeral, even victory: they all dissolve into a small, limp film of red rubber. We live and die by the pen.)

A bunch of us retired to Zak's afterward, to discuss how strange it is to find a poem that would slay them in one city flopping in another; how hard it is to decide whether you should follow your competitor's lyrical poem with a funny one, or to stay in the same mode; how fiendishly difficult it is to decide which poem should win when one of them made you stifle a laugh, and the other made you stop and think, "ahhh..."

Many things were good about this night. The novelty and fun of a new form of show, the sense of humor, Brad's sumo-referee style of hosting, and the revelation of how flexible and living the haiku is. Kevin and I were talking about modern haiku on the break. He said that while you think of traditional haiku as evoking nature, for many people now, going online is like going for a walk. So, once you're there, surfing around on the web, if you look around, you see things you can turn into haiku everywhere.

And there really is a skill to making such a limited number of syllables sound natural, and cause the audience to guffaw, murmur, or sigh.

I'd heard about other Haiku Death Matches before, and when I interviewed Rusty Priske, the Slam Master, about it a couple of weeks ago on Literary Landscape, we talked about what kind of haiku to expect. A haiku's short, and if you're going up against each other in an audience-judged competition, you go for pithy, funny, snappy, right? In Vancouver, I've been told, the competition is dominated by sex jokes.

When I got to the Mercury Lounge, they were tying balloons to the wrists of all the competitors who signed up. People were walking around counting syllables on their fingers and reading through notebooks.

Ten people were eventually signed on to the lists. I'd intended to sit back and enjoy the show, but then was asked to be a judge. "You don't have to give a grade," Brad said. "You just have to pick one poem or the other."

Well, how hard can that be? I thought to myself. I've judged at slams before but I really have a hard time giving a number grade to poetry.

I was a fool. Having to pick between two haiku was, at times, astonishingly difficult.

The competition was gleefully hosted by Brad Morden, who announced the rules: Two names would be drawn from a hat. Those two "haiku warriors" would come to the stage. Each would perform a haiku, and the judges would choose a winner (by flashing either a copy of the latest Capital Slam CD or the flyer for next week's VERSeFest). Best two out of three would take the bout. Once you lost two bouts. . . your balloon was popped. Ceremoniously. To a chorus of cries from the audience of "Aww... no! NO!" as Brad proclaimed, "We live and die by the pen!" and popped the balloon with a ballpoint.

Another rule: total silence during the bout. You could clap for the "haiku warriors" when they were called up (and as the night went on, you could hear the reaction from the audience when a particularly strong pair got called), but then Brad would call out, 'SILENCE!" and you were supposed to be quiet as the haiku, some of which were really funny, were read. This, of course, only served to heighten the hilarity as people either stifled laughs, or defied the silence rule and laughed out loud or shouted things.

Meanwhile, behind the competition, classical Japanese music played.

It was hilarious.

The haiku had a wide range: from the expected sex jokes, through pop culture references, to the stereotypical lyrical and evocative image. Some haiku warriors made their stuff up on the spot: "I love cats. Too much. / My arms are full of scratches. / Kitties, love me back!"

Others brought their books, and flipped through them madly trying to choose the right response. And then came the first balloon death. "No mercy at the death match!" Brad roared. "We live and die by the pen!"

I get the feeling he was enjoying himself.

Finally there were only four poets left standing, and we had a break. I had been surprised by what I was hearing. As a judge, I had to make a snap decision every time. The poems could be radically different, or both in similar modes: either way, it would be a serious bitch deciding which to give the win to. There were funny poems about zombies, or wistful poems about lost loves, or snappy self-referential poems - I liked Rusty's "haiku trash talking" poem, for one - or 'deep thoughts' poems (a lot of these brought out by a newcomer to the CPC scene, who went by K. G., an older man who got up to the mike each time with a sort of gravitas, and a measured, dignified, Caribbean accent, that inevitably slew the other poets, particularly if they brought a funny poem. We talked about it afterwards: If you were up against him, and all you had was a dick joke, you inevitably sounded trivial compared to his meditations on the human condition. You had to have one hell of a good dick joke to beat that.)

Which is the surprise, for me. I knew that in the Vancouver scene, the dick joke would normally win. As the night went on I saw the judging going in strange directions - not always in favor of the deep stuff, but definitely resistant to the cheap shot. I know I was giving more points to people whose phrasing sounded natural (it takes more skill to make a 5-7-5 syllable pattern sound like normal talk than to drop out the odd article because it saves a syllable, and I consciously rewarded that). I think my fellow judges were doing the same thing. Top marks, generally, would go to witty AND insightful, which was hard to go for.

My money, if I had had money riding on this thing, would have been on Kevin Matthews. He's the Master of Many Genres, and I've seen him do everything from slam to avant-garde. He's good at brevity and epigrammatic wit. And I know from his slam poems that he can do funny and perceptive at the same time. I'd have backed Kevin. And, when it came down to the final four, he was in the ranks.

|

| Final Four: Uncle Kevin, K.G., Sean O'Gorman, Rock Howell. |

And, as it turned out, K. G. took the last bout. To cries for mercy from the audience, Brad popped Kevin's balloon: then the audience called for a victory haiku from K. G., which he read from his chapbook. (He also insisted on having his balloon popped as well, while the audience shouted, "Let him keep it!" But I thought it was fitting the whole pseudo-bushido atmosphere. All things are ephemeral, even victory: they all dissolve into a small, limp film of red rubber. We live and die by the pen.)

A bunch of us retired to Zak's afterward, to discuss how strange it is to find a poem that would slay them in one city flopping in another; how hard it is to decide whether you should follow your competitor's lyrical poem with a funny one, or to stay in the same mode; how fiendishly difficult it is to decide which poem should win when one of them made you stifle a laugh, and the other made you stop and think, "ahhh..."

Many things were good about this night. The novelty and fun of a new form of show, the sense of humor, Brad's sumo-referee style of hosting, and the revelation of how flexible and living the haiku is. Kevin and I were talking about modern haiku on the break. He said that while you think of traditional haiku as evoking nature, for many people now, going online is like going for a walk. So, once you're there, surfing around on the web, if you look around, you see things you can turn into haiku everywhere.

And there really is a skill to making such a limited number of syllables sound natural, and cause the audience to guffaw, murmur, or sigh.

Wednesday, February 27, 2013

Adaptation fail

Something tells me that if a book is unfilmable, you should just, maybe, not try to make a movie out of it.

World War Z, by Max Brooks, is probably the best zombie book out there. (Although, I haven't read all of Walking Dead, to be fair.) The book is "an oral history of the Zombie War."

It's been some undisclosed number of years since the zombie threat was declared officially over, and our unnamed protagonist is a guy armed with a tape recorder, collecting the stories of people who were involved. Every story is told as a transcript from the tape: just a person speaking, starting with the doctor in China who discovers one of the early cases in a small village and is silenced by the government. Our journalist interviews human traffickers who make the problem worse, even though they suspect what's happening; intelligence officers who cover it up; the CEO of a company that knowingly sells a placebo "cure"; people who hole up in gated communities; soldiers who see action on the front lines against waves of undead; members of the world's governments who eventually have to implement the scariest, most draconian systems to ensure survival; an astronaut who spends the whole apocalypse watching helplessly from the International Space Station; and the people trying to put the world back together once the war has finally been won.

The thing I really like about World War Z is the scope of it. People from all over the world, in all levels of society, get a moment to have a voice. You watch single individuals and their choices make or break history, but you also watch what average people do (there's an autistic teenager who tells her entire story in sound effects and reenactments, which makes it worse when you realize she's reenacting the moment her mother tried to strangle her while they were hiding inside a church, rather than let her be turned.) And voices from India to Japan to South Africa to Canada get to speak.

It's a global book, and what scared me about it was that you could substitute pretty much any real threat - disease, global warming, food shortages - for the zombies and get a frighteningly plausible scenario for how the way we are as a species and society makes disaster possible.

Right. And then because the book was popular, someone made a movie. And this is the trailer. Yes, that's Brad Pitt.

1. This story is about one dude. Who is Brad Pitt.

2. This one dude seems to be pretty connected in the military. I'm guessing special ops or something. Woop,

3. This is only happening in America, and look at all the Americans! Something tells me General Raj-Singh, the Tiger of Delhi, will not be appearing. Something also tells me that the eventual Plan that saves humanity will not come from a South African white supremacist, you won't hear a character claim that Cuba's isolation helped it win the Zombie War, and we'll never hear from the Chinese nuclear sub crew or the South Asian 'snakehead.' And I will lay you money the Americans don't get their best tactical ideas from people in other countries.

4. Zombies don't run in Brooks' book (and a lot of zombie aficionados will tell you they should never run. I don't personally care, because zombies are a metaphor for every other disease and disaster, and if you want them to run, fine... but they don't run in Brooks' book.)

5. In the book, by the time the zombies are causing chaos in New York, people know what they are. They're already marketing a "vaccine."

6. Most of the book, in fact, is taken up with how things get to the point of no return when humanity almost gets wiped out. This movie appears to start pretty much at the point of no return.

7. Looks to me like things devolve pretty rapidly into "guy with gun and combat training saves world as byproduct of defending wife and children." Sure, I don't know that Brad Pitt saves the world in this movie, I've only seen the trailer, but that's the trope. And even if he doesn't literally save the world singlehandedly, when Our Hero gets Into The Fight, because he wants to protect His Family, the implication is that all that nobility makes it so the world can be saved.

Maybe World War Z is unfilmable (and why shouldn't it be? Must every good book be made into a movie?) Although I would love to have seen someone try to make it as a documentary, earnestly filmed, relying mostly on the verbal testimony of the witnesses (but you don't have to be totally low-budget: some footage from the combat cameras on the ground at Yonkers, views of the devastation, maybe cameraphone video clips of early patients or of stragglers outside the fences of the walled-off Plan compounds... even the scene where the woman is walking around in Northern Canada killing zombies as they start to thaw out of the permafrost could be really cool.) That would be a really innovative zombie movie. This... well, I'm wondering what arrangement they made with Max Brooks. About all I see that's similar is the title.

World War Z, by Max Brooks, is probably the best zombie book out there. (Although, I haven't read all of Walking Dead, to be fair.) The book is "an oral history of the Zombie War."

It's been some undisclosed number of years since the zombie threat was declared officially over, and our unnamed protagonist is a guy armed with a tape recorder, collecting the stories of people who were involved. Every story is told as a transcript from the tape: just a person speaking, starting with the doctor in China who discovers one of the early cases in a small village and is silenced by the government. Our journalist interviews human traffickers who make the problem worse, even though they suspect what's happening; intelligence officers who cover it up; the CEO of a company that knowingly sells a placebo "cure"; people who hole up in gated communities; soldiers who see action on the front lines against waves of undead; members of the world's governments who eventually have to implement the scariest, most draconian systems to ensure survival; an astronaut who spends the whole apocalypse watching helplessly from the International Space Station; and the people trying to put the world back together once the war has finally been won.

The thing I really like about World War Z is the scope of it. People from all over the world, in all levels of society, get a moment to have a voice. You watch single individuals and their choices make or break history, but you also watch what average people do (there's an autistic teenager who tells her entire story in sound effects and reenactments, which makes it worse when you realize she's reenacting the moment her mother tried to strangle her while they were hiding inside a church, rather than let her be turned.) And voices from India to Japan to South Africa to Canada get to speak.

It's a global book, and what scared me about it was that you could substitute pretty much any real threat - disease, global warming, food shortages - for the zombies and get a frighteningly plausible scenario for how the way we are as a species and society makes disaster possible.

Right. And then because the book was popular, someone made a movie. And this is the trailer. Yes, that's Brad Pitt.

1. This story is about one dude. Who is Brad Pitt.

2. This one dude seems to be pretty connected in the military. I'm guessing special ops or something. Woop,

3. This is only happening in America, and look at all the Americans! Something tells me General Raj-Singh, the Tiger of Delhi, will not be appearing. Something also tells me that the eventual Plan that saves humanity will not come from a South African white supremacist, you won't hear a character claim that Cuba's isolation helped it win the Zombie War, and we'll never hear from the Chinese nuclear sub crew or the South Asian 'snakehead.' And I will lay you money the Americans don't get their best tactical ideas from people in other countries.

4. Zombies don't run in Brooks' book (and a lot of zombie aficionados will tell you they should never run. I don't personally care, because zombies are a metaphor for every other disease and disaster, and if you want them to run, fine... but they don't run in Brooks' book.)

5. In the book, by the time the zombies are causing chaos in New York, people know what they are. They're already marketing a "vaccine."

6. Most of the book, in fact, is taken up with how things get to the point of no return when humanity almost gets wiped out. This movie appears to start pretty much at the point of no return.

7. Looks to me like things devolve pretty rapidly into "guy with gun and combat training saves world as byproduct of defending wife and children." Sure, I don't know that Brad Pitt saves the world in this movie, I've only seen the trailer, but that's the trope. And even if he doesn't literally save the world singlehandedly, when Our Hero gets Into The Fight, because he wants to protect His Family, the implication is that all that nobility makes it so the world can be saved.

Maybe World War Z is unfilmable (and why shouldn't it be? Must every good book be made into a movie?) Although I would love to have seen someone try to make it as a documentary, earnestly filmed, relying mostly on the verbal testimony of the witnesses (but you don't have to be totally low-budget: some footage from the combat cameras on the ground at Yonkers, views of the devastation, maybe cameraphone video clips of early patients or of stragglers outside the fences of the walled-off Plan compounds... even the scene where the woman is walking around in Northern Canada killing zombies as they start to thaw out of the permafrost could be really cool.) That would be a really innovative zombie movie. This... well, I'm wondering what arrangement they made with Max Brooks. About all I see that's similar is the title.

Tuesday, January 29, 2013

A non-slam poet goes to the slam

[insert usual stuff about how long it's been since I posted here]

Last fall I competed in the first round of the VERSe Ottawa Women's Slam Qualifiers, one of a set of three qualifying rounds to pick the twelve finalists for the 2013 Women's Slam Finals. Mostly, I competed because I support the idea of having a women's slam in Ottawa, for a lot of reasons, and because it was VERSe Ottawa and I want to support them (having worked for them in their second year), and because the coordinators are friends of mine.

But it was strange, because I had never been in a poetry slam before. Despite attending a lot of them, talking about slam a lot in reviews and on my radio show, and knowing a whole lot of people in the Ottawa slam scene, I had never felt like I needed to actually compete. "My poetry's not 'slam,'" I said, and generally, it isn't. But I had memorized several of my poems, for the three-woman show Chasing Boudicca that I was in a couple of years ago, and as a challenge for a couple of Kymeras shows. I have a bit more experience with the format now than when I first got into the scene, because I really got into story slam with Once Upon a Slam, and even came in second in the finals last year. But poetry's different somehow from storytelling, and slam in Ottawa is really established and the people who do it are really good. And I know how different my style is from the style of most people who slam.

I reworked a poem to make it 'slammier' that night: I performed a sort of mashup of two poems from the Chasing Boudicca series, knowing that the central poem (the angriest and most personal of the series, therefore the easiest to make into a slam piece) was too short. (A poem that comes in at less than about two minutes leaves the audience feeling cheated, in my experience: you're supposed to really push that three-minute limit. It's why so many slam poets talk so fast: they're cramming the poem into the maximum allowable time.)

So I added bits from another one, and while I thought the tone change in the middle was a little odd, it went over pretty well: not so much the second-round poem, my jokey, steampunky "The Scientifically Minded Young Lady's Letter to Her Suitor; or, A Gentleman's Warning." Note to self: Victorian-esque rhyme schemes don't go over well with a crowd used to hip-hop polysyllabic rhyme.

Anyway, I was surprised at the end of the night to find that I'd come in fifth. Not quite in the final four, who would go on to the finals. But nearly. I did a joking, comic-booky, "Whew!" forehead-wiping gesture. Dodged a bullet.

Except, Rusty (the coordinator) reminded me, someone could always drop out. And then I'd be back in. Depending on rankings.

And guess what.

Last Friday, I got a message from Rusty rather early in the morning, saying someone had had to pull out of the finals the next night, and he knew it was short notice, but would I be willing to slam?

I have a rule about scary things I might not otherwise have done, which I get challenged/asked/nudged to do: I tend to do them. So I checked to see if I could repeat something I'd done before (knowing that the "Chasing Boudicca" piece had been my strongest last time) and then said yes. I was at work: I would have Saturday morning, and a bit of the afternoon, to memorize my second poem and rehearse them both.

So I did that. I'm glad I'm pretty good at memorizing things: I wasn't entertaining any delusions about winning, which was kind of liberating really. But I didn't want to embarrass myself. I knew the Chasing Boudicca one had gone over well, so I reworked it a little again and rememorized it, and then I picked a lyric, pastoral, quiet, evocative little poem I wrote about being home in New Brunswick for the summer and working in the garden. Rusty said that when I performed it, he thought, "Well, this is interesting... it's not a slam poem. Just don't hate on it, judges!"

I sort of knew that I was, as I often am, being the slightly strange, foot-in-both-worlds poet. In the poetry scene in Ottawa, I'm neither fish for fowl, really. And I knew almost no one in the audience would recognize me, the way they would the rest of the competitors. V? Sure. Dimorphic? Sure. D-Lightfull? yup. Kate Hunt? Who the hell? Where'd she come from? So I figured I might as well go with that, and do something that would be totally different.

In the end, it cost me a couple of points - one judge gave me the lowest individual score of the whole night on it. But then Brad Morden yelled "READ A BOOK!" at him/her, which made me smile. And at the end of the round, I wasn't the lowest score of the night so far.

Then in the second round I got lucky and was drawn late in the round (you want to be later, because no matter what, scores creep upwards throughout the night) and brought out the Boudicca poem, and the judges dug it. It's definitely slammier, whatever that means: something about it being faster and (in this case) angrier and direct and about personal emotions, and ending with a bit of a bang. The judges liked it - all in the 9.something range. Which boosted me a lot, and I wound up coming in eighth overall, out of twelve, when the final scores got tallied up.

Not having had any delusions about winning, I was actually really impressed with that. I don't slam. Everyone else performing were experienced, and had competed at regular slams through the year. I've had a lot of experience at storytelling over the last year or so, but still, I was amazed.

And what it did was to remind me of a couple of things. One: I don't write enough lately. Or, really, at all. And two - maybe I should try this slam thing, just to see if I can do it. Apparently I don't make a half bad showing with a day's notice. . . so maybe I should give it a try?

Last fall I competed in the first round of the VERSe Ottawa Women's Slam Qualifiers, one of a set of three qualifying rounds to pick the twelve finalists for the 2013 Women's Slam Finals. Mostly, I competed because I support the idea of having a women's slam in Ottawa, for a lot of reasons, and because it was VERSe Ottawa and I want to support them (having worked for them in their second year), and because the coordinators are friends of mine.

But it was strange, because I had never been in a poetry slam before. Despite attending a lot of them, talking about slam a lot in reviews and on my radio show, and knowing a whole lot of people in the Ottawa slam scene, I had never felt like I needed to actually compete. "My poetry's not 'slam,'" I said, and generally, it isn't. But I had memorized several of my poems, for the three-woman show Chasing Boudicca that I was in a couple of years ago, and as a challenge for a couple of Kymeras shows. I have a bit more experience with the format now than when I first got into the scene, because I really got into story slam with Once Upon a Slam, and even came in second in the finals last year. But poetry's different somehow from storytelling, and slam in Ottawa is really established and the people who do it are really good. And I know how different my style is from the style of most people who slam.

I reworked a poem to make it 'slammier' that night: I performed a sort of mashup of two poems from the Chasing Boudicca series, knowing that the central poem (the angriest and most personal of the series, therefore the easiest to make into a slam piece) was too short. (A poem that comes in at less than about two minutes leaves the audience feeling cheated, in my experience: you're supposed to really push that three-minute limit. It's why so many slam poets talk so fast: they're cramming the poem into the maximum allowable time.)

So I added bits from another one, and while I thought the tone change in the middle was a little odd, it went over pretty well: not so much the second-round poem, my jokey, steampunky "The Scientifically Minded Young Lady's Letter to Her Suitor; or, A Gentleman's Warning." Note to self: Victorian-esque rhyme schemes don't go over well with a crowd used to hip-hop polysyllabic rhyme.

Anyway, I was surprised at the end of the night to find that I'd come in fifth. Not quite in the final four, who would go on to the finals. But nearly. I did a joking, comic-booky, "Whew!" forehead-wiping gesture. Dodged a bullet.

Except, Rusty (the coordinator) reminded me, someone could always drop out. And then I'd be back in. Depending on rankings.

And guess what.

Last Friday, I got a message from Rusty rather early in the morning, saying someone had had to pull out of the finals the next night, and he knew it was short notice, but would I be willing to slam?